Judith Joy Ross

SEP.24.2021 ──────── JAN.09.2022

Judith Joy Ross

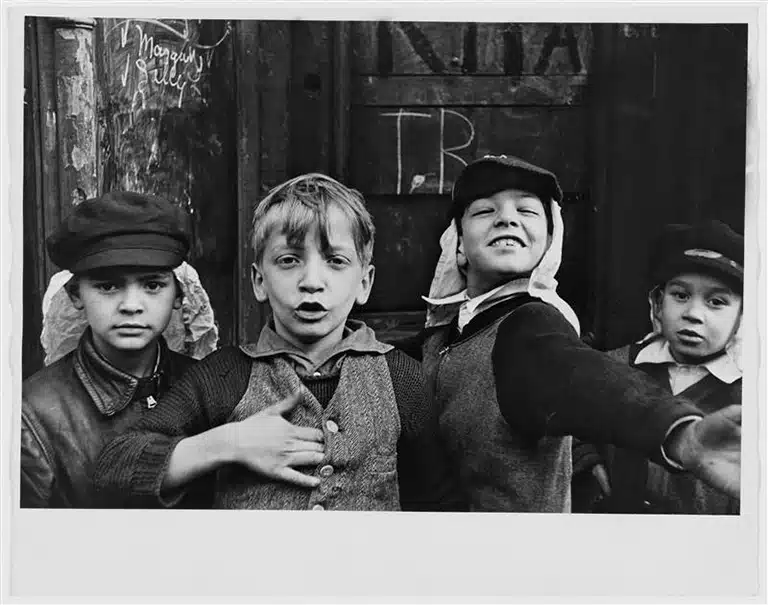

Untitled, Eurana Park, Weatherly, Pensilvania, 1982

© Judith Joy Ross, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Más detallesMenos detalles

Ross began taking photographs of people as a way of understanding the emotional world of the strangers around her. In the early 1980s, after several trips to Europe, Ross acquired an 8×10-inch view camera in order to make portraits of ordinary people in public places. Sharing an artistic lineage with the work of Lewis Hine, August Sander, and Diane Arbus, Ross’s images mark a pinnacle of this genre, attesting in the ability of a portrait to glimpse the present, past, and even future of its subject.

Ross’s portraits are made according to a personal impulse and innate interest in the people she meets. The remarkable sense of transparency of the portraits comes from the connection that the photographer establishes each time with the portrayed. Her portraits are largely made in the context of series, ranging from children in Eurana Park, visitors at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, members of the United States Congress during the Iran-Contra affair, students and teachers in the schools of Hazleton, or specific places in northeastern Pennsylvania, where she was born and raised, and where she still lives today.

Curator: Joshua Chuang.

View camera: In the early 1980s, Ross acquired an 8×10-inch view camera, whose deliberateness allowed her to engage her subjects both intimately and at a remove. She sees her portraits as a kind of collaboration: each sheet of exposed film memorializes a moment in an essentially fleeting, wordless exchange with a stranger. “Both of us together—we make the picture,” Ross has said. “They’re giving me, I’m getting. I’m encouraging them, they give me more. We both might actually be in love for a few seconds. I’ll never see them again.”

Without sentimentality or prejudice, Judith Joy Ross makes portraits as a way to understand the emotional truths of the people she encounters. Ross does not work in a studio, but on the street, in parks and other public spaces.

Asking questions: Although she uses a tripod-bound view camera, Ross’s portraits are spontaneous—made, as she has said, “to know something about someone.” Many of her series have been spurred by inner existential or civic inquiries: how to deal with pain and injustice, what makes life worth living, and how a person’s life might play out, decades into the future.

Ordinariness: Ross’s photographs are devoted to the ordinary and the everyday. She neither glorifies nor casts judgement upon her primarily working-class subjects. Instead she attempts to identify with what makes them human.

Personal: Throughout her career, Ross has been drawn to photograph in places that have played key roles in her own biography. After the death of her father, she photographed in Eurana Park, a small grove in Weatherly where she used to play with her siblings when they were young. The memory of her father also moved Ross to return to Nanticoke, a town where her father managed a variety store, and in Freeland, where he was born. One of Ross’s most significant projects was carried out in the very Hazleton public school buildings that Ross attended when she was a child.

If you would like to contact the Communication Department to request the press dossier, high-resolution images or for any other matter, please complete the form below giving the name of the medium/media for which you require this information.

The exhibition catalogue includes reproductions of all photographs on display, the majority of which have never before been exhibited or published.

The book features essays by the exhibition’s curator Joshua Chuang, and renowned art historian Svetlana Alpers, as well as an illustrated chronology by Adam Ryan. A personal reflection by Addison Bross, friend of the photographer, accompanies his portrait reproduced in the catalogue.

The catalogue is available in both Spanish and English. The English language edition is co-published with Aperture.